Local filmmaker documents how human connection is the antidote to addiction

The most rewarding aspect of this job is having the opportunity to interview people who are doing their utmost to make a difference for the greater good. It is an honor to sit with people who are devoted to selflessly building community.

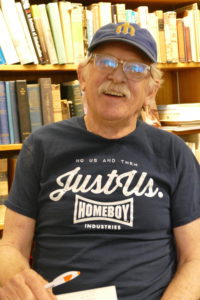

A few months ago, Paul Steinbroner, a local documentary filmmaker, reached out to me after I wrote about Father Greg Boyle, the Jesuit priest who founded Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles. Through that organization, Boyle helps felons and gang members to find their own humanity, worth and sense of purpose.

Steinbroner captured the Home Boy experience and Greg Boyle’s philosophy in a 30-minute documentary that challenges the viewer to consider these individuals differently – as human beings who have been through horrendous situations in their lives, done bad things, but who find kinship and belonging. The success stories are amazing.

Steinbroner is producing a six-part series focuses on addiction as a spiritual disease that belonging to a healthy community is the opposite of addiction. Upcoming segments were filmed at a Native American Treatment Center in Washington, Recovery Cafe in Seattle, a synagogue in Los Angeles and with the Rev. Richard Rohr in New Mexico. This month his crew is off to San Diego to film the Standown, a three-day bivouac with every health service a veteran could want. The event provides them with the hope that they have meaning and purpose, plus the opportunity to get into a long-term treatment program.

It is that journey from darkness into the light that has captivated and held the attention of Steinbroner. He is driven to telling these stories and making a difference in communities like ours by showing us successful efforts that are based on love rather than hate and judgment.

People who suffer from addiction have survived awful things but when they become willing to change they become tender, loving human beings,” said Steinbroner. “It’s the opposite of the zombie story. They go from being a zombie to a human being.” When they come to Homeboy after prison or from a gang, they come from a hopeless place in life. And the stories of what they have survived — heroin-addicted parents, horrible abuse, violence and other traumas – are wrenching, Steinbroner told me. “When the outside stuff goes away (drugs and alcohol), they go into a free-fall at first,” he told me. “It takes months for the brain to come back.” Homeboy Industries and other similar programs give them that time to find their own humanity.

As a filmmaker, Steinbroner talks about the “tender, amazing transformative experiences” that he witnesses and films. Being at Homeboy, he told me, is an inspiration and a gift. In the film, Boyle says that “we want to take seriously what Jesus took seriously, which is inclusion, nonviolence, unconditional loving kindness, and compassion and acceptance. What happens in their recovery is finding a sense of purpose, dignity and hope, regardless of what crimes they committed or other things that they have done.

In the film, Boyle talks about the Homeboy Industries approach: “This place wants to stand against forgetting that we belong to each other because at the root of all that is wrong with the world is born of this notion that there just might be lives out there that matter less than other lives.”

Steinbroner is doing remarkable work and he is eager to find ways to let others in our communities discover what is possible with the disaffected and disowned in our own neighborhoods. He hopes to have some showings of his films in North Central Washington to start a discussion about how we can think differently about those at the margins.

To see some of what has been going on over the past year, check out the website and please share it with others who have been negatively affected by a loved one’s addiction.

To steal a phrase from Boyle, Hope has an address calledfromdarkness.com. Let’s try and figure out how we can get this film screened here as an opportunity to discuss this health crisis affecting all the people here in North Central Washington.