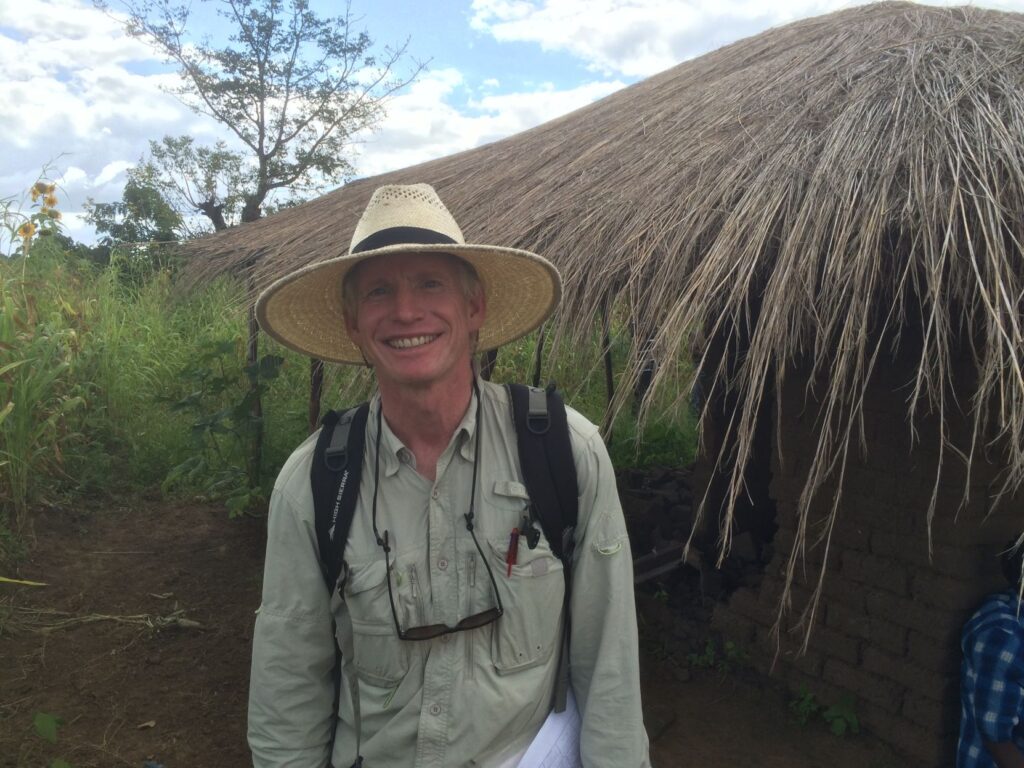

Garn Christensen’s tough childhood shows why we can’t give up on kids who struggle

Eastmont School District Superintendent Garn Christensen has much to be proud of during his tenure at the school and in the community. He took the position when it had been a revolving door and brought stability and a thoughtful, systematic and understated approach to the district.

Creating order out of chaos is something he learned through his rather unorthodox upbringing and topsy turvy journey through the educational system in Utah. Christensen’s early years were the epitome of instability. His parents divorced when he was 11, and his father dropped out to become a hippie in a different state while his mother remarried a fundamentalist art professor. They were survivalists convinced the end of the world was near. At 15, he ran away from home and essentially was a homeless student. If he wanted to go to school, he had to find a way to get there, he recalled.

Often,all it takes to help a struggling student is one caring mentor. For Christensen, alternative school teacher Mickey Ibarra, who later worked in the White House, was a catalyst. “I would have never graduated from high school had it not been for (Ibarra),” he said. Christensen was able to test his way through classes and ultimately ended up attending BYU as a very rebellious 16-year-old. “I was there a couple of semesters and had a lot of fun — too much fun,” Christensen recalled. He engaged in what might be described as a variety of “monkey wrenching” activities and ended up being asked to leave. He also owed a significant amount in restitution. To pay this back, he became a seasonal ranch hand for a livestock company and returned to school at the University of Utah, where he also worked as a burn tech at the Intermountain Burn Trauma Center.

This would become a major theme in his life — challenging circumstances becoming a crucible in which he developed the resilience to bounce back. With virtually no experience, he ended up as a rafting guide and learned a valuable lesson — it was OK to flip a raft, but if he lost any equipment in the process or put lives at risk, he’d lose his job.

These formative experiences taught him valuable life lessons about building relationships with people who have radically different views, leading others by listening deeply, taking responsibility for his actions and, perhaps most importantly, giving people the benefit of the doubt. Christensen told me he tried to pay particular attention to support who didn’t have advocates, such as involved parents, or organizations standing with them, so that they weren’t at a disadvantage.

“I respect people for having differences,” Christensen told me, “and I can introduce myself as an educated hippie or an educated redneck.” He characterized part of his job as superintendent as trying to structure conflict so that people could be heard. He likes to think of the superintendent’s office as the bottom of the district with the work of the teachers as the critical front line of education, a point of view I appreciate.

One of his highest priorities as superintendent is that kids feel safe and connected in school. At Eastmont, caring for kids would sometimes lead to school staff writing down the names of every student and making sure somebody had a meaningful connection with them. He’s also a big advocate for providing equity rather than equality. An equity approach means striving to give kids the support they need to grow rather than every kid getting the same support. As one example, only kids with hearing impairment require devices to help them overcome that challenge. This is no different than adults who are great readers, but only if they have their reading glasses.

Christensen doesn’t buy the argument that our schools are failing kids. “I have watched education go from being good, to what I would say is really, really good right now,” he said. “We’ve got amazing teaching happening now,” he added.

The last few years have been politically more divided in the country and education has been in the crosshairs in the culture wars. Christensen said it’s important that schools be “Switzerland” and not “lean to one side or the other of the political spectrum.”

“We’re going to teach those basic core academics,” said Christensen. The focus is one whether students are competent writers, skilled readers, are comfortable with math, good listeners, communicate effectively and take advantage of experiences like drama, art, music and sports.

Christensen leaves a strong foundation for his successor, Becky Berg, to build upon. His story is a reminder that we should not write off kids who are struggling. It’s our educators who are usually the ones to help them pick up the pieces.