The remarkable story of Dick Buscher’s impact on wilderness and recreation in NCW and beyond

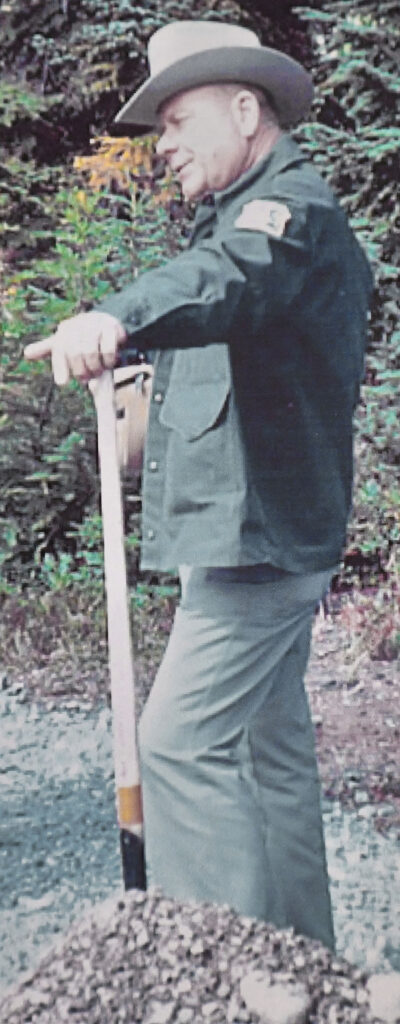

Richard “Bush” Buscher of the U.S. Forest Service had an enormous impact on the development of multiple wilderness areas, including the renowned Alpine Lakes Wilderness and the William O. Douglas Wilderness, and left a legacy of leadership and constructive engagement.

Buscher, now 87, and living in Oregon, made an indelible impact on the Forest Service, the landscapes and the people with whom he connected and befriended.

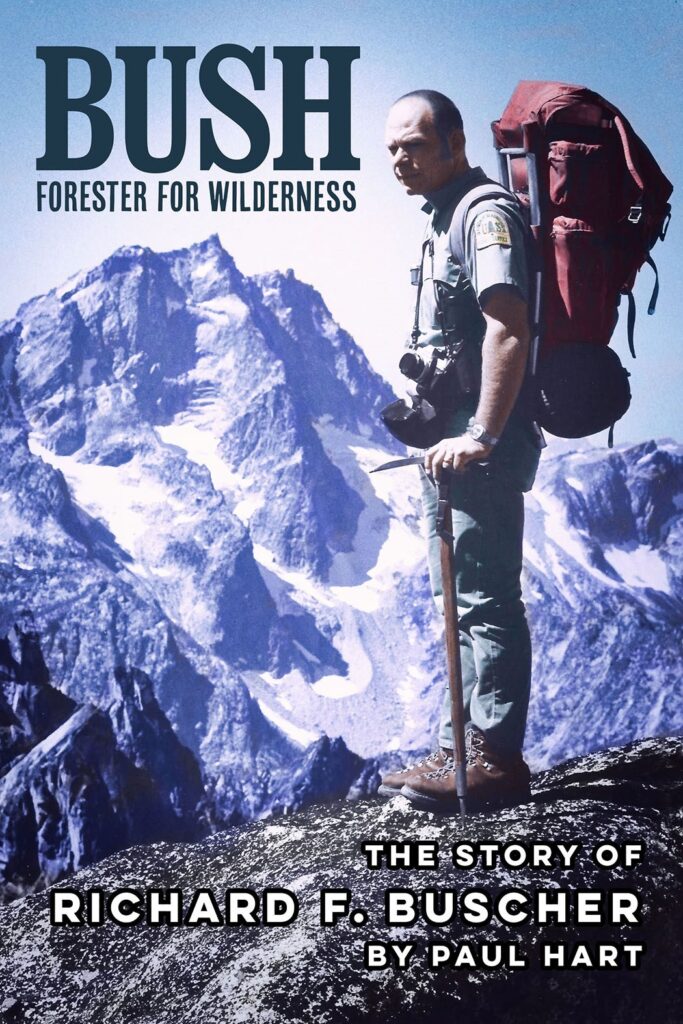

Paul Hart, the long-time public information officer at the Wenatchee National Forest ,spent the last two years interviewing Buscher and has just self-published Buscher’s story in a book titled Bush: Forester for Wilderness. It is a fascinating read that is available in local bookstores and through Amazon.

Buscher was the deputy supervisor of the Wenatchee National Forest from 1974-84. Trained as a forester, he came to see the value of wilderness as something essential for our society — places that were to remain either untouched or lightly touched by humans.

Buscher, never been one to mince words, writes: “Why is wilderness important? Because we’ve screwed up all the rest of the country and we ought to leave a little bit alone.” It’s hard to argue with Buscher on that point.

Hart was the perfect person to write this story. He developed a close working relationship and friendship with Buscher during his time in North Central Washington, a relationship that continued through the rest of their careers and into retirement.

Buscher, a native of Iowa, started his career helping to develop a management plan for the Oregon Dune National Recreation Area, designing timber sales and heading firefighting crews. After he left the Wenatchee National Forest, he became deputy director for Recreation and Wilderness for the Pacific Northwest Region of the Forest Service.

During his remarkable career, Buscher had memorable encounters with Forest Service leaders, congressmen and senators, Chief Justice William O. Douglas and Lady Bird Johnson. The stories he tells about those meetings as well as his detailed recollection of the people he worked with and connected with along the way creates a deep understanding about Buscher’s values and his commitment to serving the public.

I was particularly intrigued with his recollections of what it took to do the planning for the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. He was assigned that job and given a measly two years to get the job done, which was accomplished. He and his small team walked the ground rather than develop the plan from afar and used a mapping process of layering various land values, such as timber value, recreation and wildlife to arrive at the best boundaries of the Wilderness.

The book is also filled with stories of a time in which the Forest Service was less constrained by rules and regulations and more responsive to the local community. He recalled a particular effort in which they citizens to cut grand fir Christmas trees as a way of fostering a healthier forest while building stronger community ties. He recalled happily monitoring children sledding while their parents were out cutting trees. It’s hard to imagine that happening these days.

Buscher was an idea man without equal, Hart told me. “He was always looking for better ways to do things,” he added.

Buscher helped drive a different mindset at the Forest Service, coming into it when it was primarily producing timber for industry and evolving that mission into managing the forests for multiple uses.

Buscher wasn’t an avid rule follower but he remained true to the principle of making decisions based on the public interest.

As for the future of our natural resources and particularly wilderness, Buscher remains deeply concerned. “We’re forgetting how to read books. We’re forgetting how to do inter-human exchanges…talking face to face,” Buscher said. “Does the Forest Service have a future? I really wonder,” he writes.

We should view that sobering assessment with a renewed commitment to follow in the footsteps of Dick Buscher — putting the public interest first.