The 1918 flu epidemic, as told in the pages of The Wenatchee Daily World

I was curious to learn what lessons might be gleaned from how the Spanish Influenza pandemic impacted the communities of the Wenatchee Valley and North Central Washington in 1918.

I dug through the archives of The Wenatchee Daily World with the help of indexes that The World’s late historian, Bruce Mitchell, compiled. I found more than 50 stories, beginning on Oct. 9, 1918 and ending on Feb. 7, 1919 that chronicled the see-saw battle with the virus.

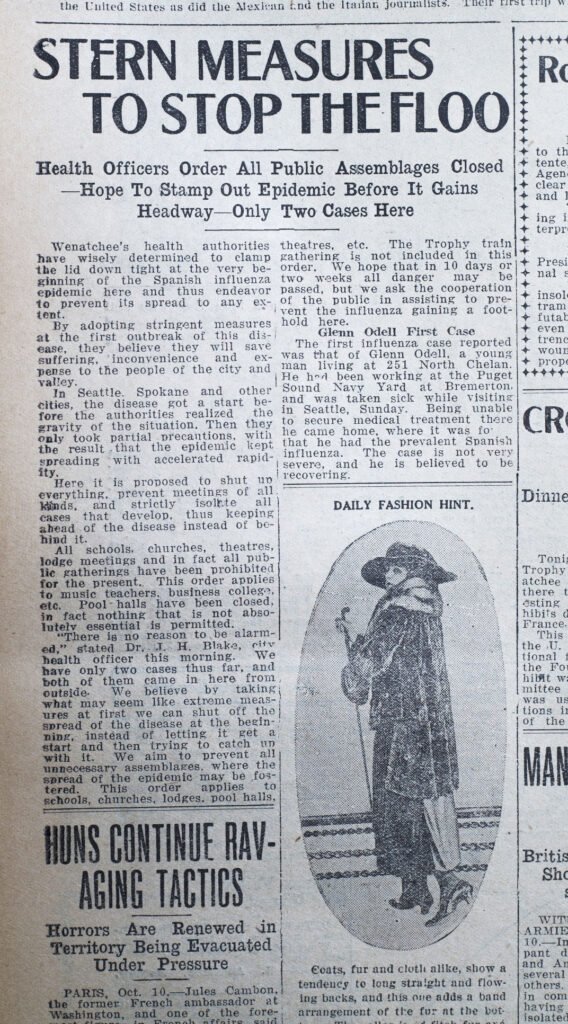

The first story was about health officials shutting down all public gatherings after the first two cases were reported and isolating every person who came down with the flu. “There is no reason to be alarmed,” County Health Officer Dr. J.H. Blake told The World.

There was optimism that the epidemic might be over within a few weeks, but that turned out not to be the case. In fact, the valley would see periods of reducing restrictions followed by an increase in cases as the epidemic worked its way throughout the communities.

A place was needed in Wenatchee for an emergency hospital to handle the patient load and the Odd Fellows Hall on Wenatchee Ave. was used for that purpose. It opened on Oct. 22, 1918.

The first reported deaths were reported on Oct. 23. Ray Wilder, 24 and W.F. Cox, both of Cashmere succumbed to the flu. Cox was a fruit worker from California who was working the apple harvest. In that same issue, the death of Catholic Father Daniel P. Kelly was announced. He had been visiting gravely ill influenza patients when he came down with the illness.

More deaths were reported at about that time in Peshastin, Cashmere and Waterville.

The World told the story of the emergency hospital in the Oct. 25 edition of the newspaper. A baby was born to one of the first patients in the hospital and had survived. The families of some patients brought their own beds, bedding and supplies. “Mrs. Olson, the nurse in charge, is one of the busiest women in the city,” according to the paper.

In the Oct. 30, the paper reported that a total of 12 patients recovered at the Odd Fellows emergency hospital and four others had died, a positive accomplishment to be celebrated.

By the end of October, the “Influenza situation slightly improved,” according to The World, but on Nov. 1, the paper reported an increase in flu cases prompted stricter regulations.

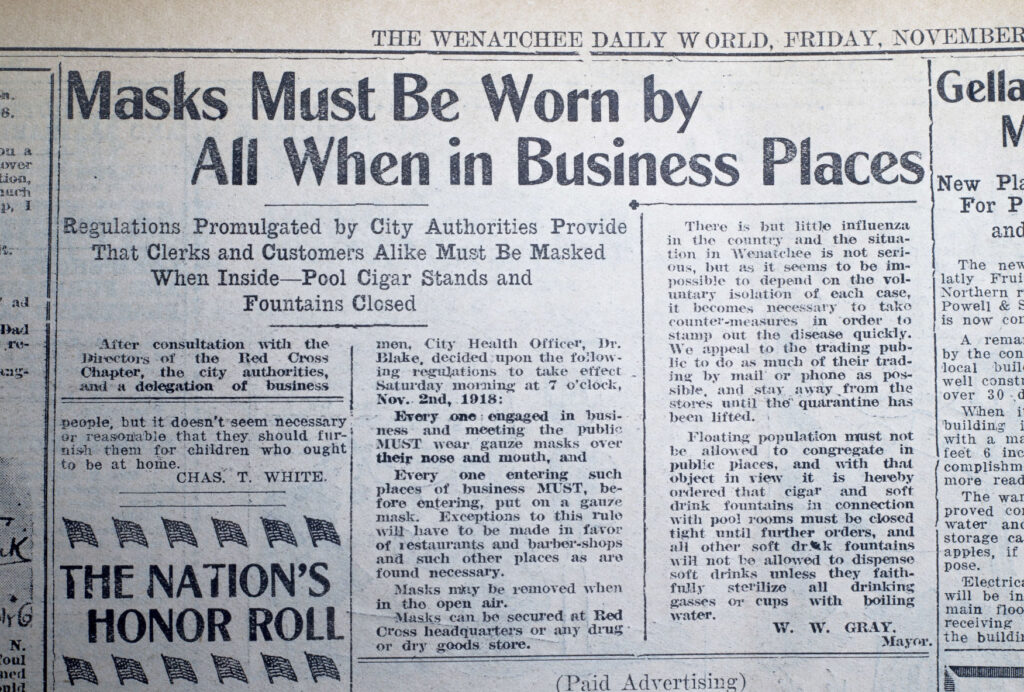

To reduce the spread of the flu, masks were required of election officials for the 1918 election and in early November, the state required masks to be worn.

One of the interesting stories done by The World was a call for chickens to be donated to the emergency hospital to help feed the patients.

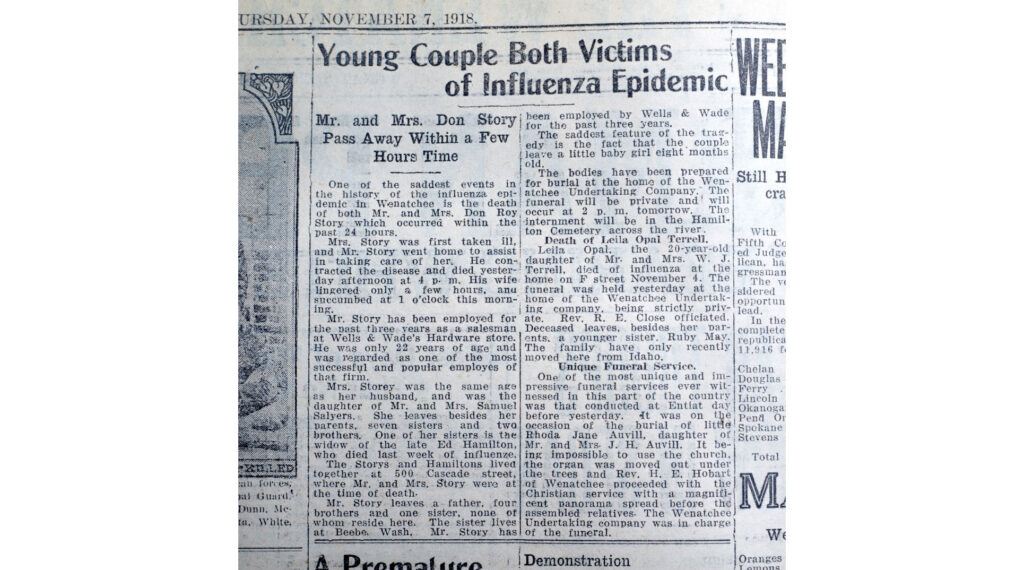

The headline on Nov. 7 was promising: “Believe that crest of influenza past.” But that was overly optimistic. In that same edition, the World published a poignant about the deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Don Story, a young couple. He was a clerk at Wells and Wade Hardware, and they lived on Cascade St. Public Health officials required the wearing of masks in public places.

The paper also reported an unusual funeral service for little Rhoda Jane Auvil, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. J.H. Auvil of Entiat. Since indoor funerals were banned, the church organ was moved outdoors under the trees and Rev. H.E. Hobart of Wenatchee proceeded with the service.

The flu situation got so perilous by Nov. 9, that the city of Wenatchee was closed up for three days to halt the spread of the outbreak.

Three days later, on Nov. 12, perhaps thinking that they had the virus licked, it was announced that county schools would be opening shortly. Flu mask regulations were relaxed. Once again, the flu started flourishing. Six days later, eighteen new cases were reported.

Meanwhile, the community was stepping up to support the hospital and patients with donations of food. The epidemic was particularly hard on low income people who were living in cramped housing and had difficulty isolating.

By early December, attention in the community turned to the problem of “bad sanitary conditions.” The Roosevelt Hotel Building had been condemned by the city but was still serving as a rooming house and a number of flu cases occurred there.

By Dec. 11, “Flue quarantine is now in full blast and effect,” the World reported. Penalties for failing to report an existing case would be enforced, said the paper.

Three days later, officials announced that the quarantine was working and that “disease rapidly decreasing and now under control.”

In late December, pressure started mounting to open schools, but that wouldn’t happen until Feb. 3, the same date that the influenza quarantine was lifted.

The influenza outbreak put a tremendous strain on the local hospital in 1918, just like it is happening today with the expected $26 million deficit Confluence Health is facing. During the flu epidemic, The World reported that Chelan County stepped up to help pay a third of the deficit of the emergency hospital.