Layman connects us with Native American history, culture

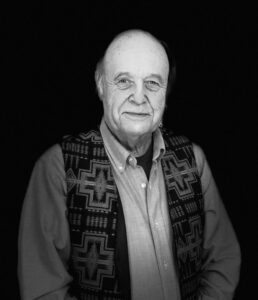

Retired mental health counselor Bill Layman has been instrumental in helping our communities begin to recognize and appreciate a forgotten part of history in North Central Washington — that of the native peoples who were here for hundreds of generations before those of us of European descent showed up.

I spoke with Layman, who is the author of books such as “Native River: The Columbia Remembered” for my Art of Community NCW podcast recently. The interview with Bill was a rich conversation that touched on his background in the Midwest and early interest in the Columbia River, his growing interest in the lost past of Native Americans in our region and how we can learn and grow from valuing their relationship with the natural world.

You can hear the podcast by accessing artofcommunityncw.com, which features stories of community building in our region.

One thing I had not fully appreciated in Bill’s story was the significant contribution made by his wife, Susan Evans, to this work. Bill considers this work to be a team effort and I wish I had included her in the interview.

A native of Dayton, Ohio, Bill got his first taste of Native American culture and history during a visit to Fort Ancient on the Great Miami River. In the fifth grade, he had his first taste of the Northwest. He sent away for materials from Washington State for a school project and was captivated by a photo of the now-submerged Celilo Falls. That image stayed with him. In 1979 Layman and Evans headed west to Washington in their camper van, and, after running short of funds, they decided that Wenatchee would be a good place to live.

Layman has long felt strong commitment to contribution in his heart — a desire to make a difference.

“My interest in Native American cultures arose out of that sense that was a story to be told here … that might carry meaning for others,” Layman told me. “The soul of a place is embodied in its landscape,” he added.

During his investigations, he ran across Harold J. Cundy’s sketches of Rock Island’s pictographs and petroglyphs and photographs of Rock Island by early Wenatchee photographer A.G. Simmer. Later he discovered a long-lost cache of photographs taken of the Columbia River in 1891, before the river was turned into a collection of reservoirs by hydroelectric dams.

“The free-flowing Columbia was once like a beautiful beaded necklace where every bead was a place of great beauty and significance— these were places like Celilo Falls and Kettle Falls,” Layman said.

That inspired his widely recognized work “River of Memory” which brought undammed Columbia back to life. “It seemed to me that to know this place of ours we had to see the entire river as it once was,” Layman said.

The recent involvement of Elder Randy Lewis in retelling the stories of the Wenatchi Band has been instrumental in reconnecting us to that history. As a descendant of Samuel Miller of the Miller-Freer Trading Post, Lewis is deeply interconnected to tribes throughout the Columbia Plateau, Lewis’s retelling of stories from the oral native traditions brings to life events surrounding the geologic features of our region.

Layman and Lewis collaborated on a recent book published by the Wenatchee Museum, “Red Star and Blue Star Defeats Spexman.”

Part of his reconnection to this Native American past involves our engagement with nature. Layman is an outspoken and forceful advocate for environmental sustainability and addressing the challenges of climate change. The motivation for his work centers around questions like: “How can we best love this place and. how can we honor and care for it?”

Asked what he is grateful for at this time, he said the following: “Our living on this marvelous planet that is home to such a great diversity of Creation, where we human beings embody a desire not just for survival but for belonging, connection and love.”

Layman sees a great opportunity with the city of Wenatchee’s proposed Columbia Gateway Project that would include a second bridge across the Wenatchee River to enhance traffic flow. Spin-offs connected to such a project might include tying restoration efforts with the Horan Natural Area to the dream of building an environmental center and creating a designated place that would invite the region’s Native American descendants to visit and reconnect with this valley.

I truly appreciate Layman’s vision and his sense of multi-generational responsibility. This, rather than unfettered consumption, would bring us closer to living sustainable, meaningful lives.