Ex-inmate from East Wenatchee has some ideas about improving our prisons

Forty years ago as a young reporter at The World, I was assigned the task of covering a rather unique graduation at the Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla.

Kelley Messinger, a graduate of Eastmont High School, was graduating with honors from Washington State University at that ceremony. Messinger had been convicted, wrongly as it turns out, of killing his wife and spent 10 years until Gov. Dixy Lee Ray commuted his sentence in 1981. She’d been told the investigation of the crime was fatally flawed and an example of what law enforcement should not do.

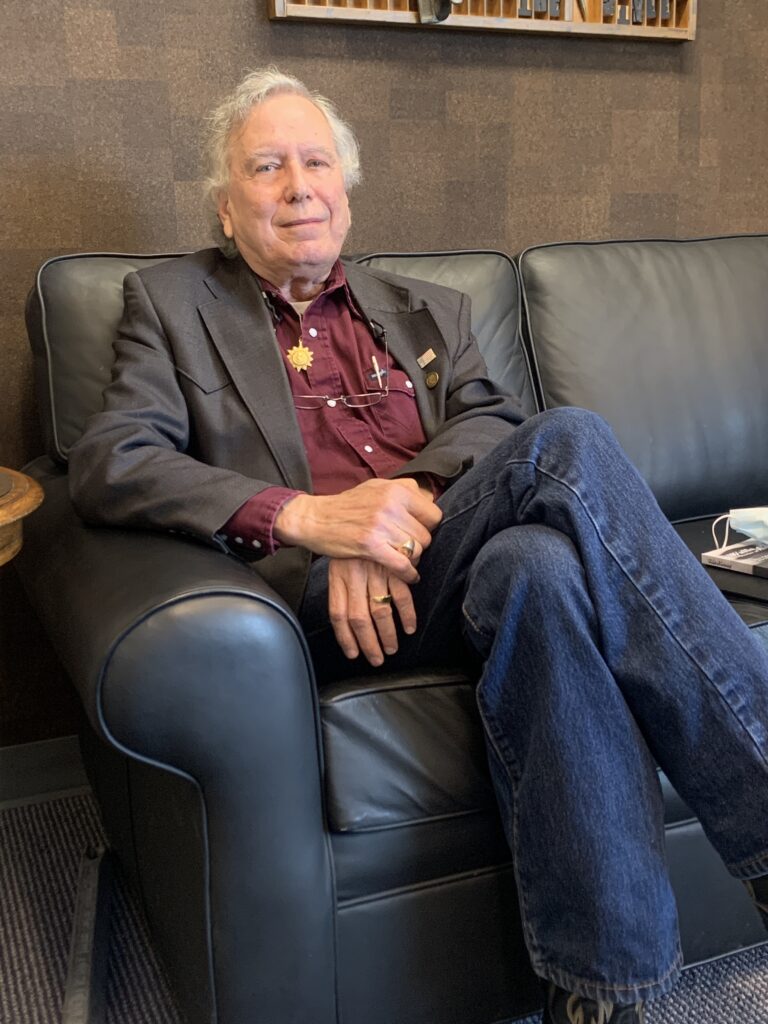

Over the years, I had occasionally wondered what had become of Messinger and discovered that he was a successful business owner and stand-up community member.So it was quite a surprise when one day this spring Messinger walked in the front door of the Wenatchee World office at 14 N. Mission St. and asked to speak with me. You could have knocked me over with a feather.

Messinger wrote a book about what life was like at the penitentiary during a time when the state was involved in a radical experiment of letting inmates control the prison, something that was borrowed from a Scandinavian country without considering whether the prison populations were equivalent.

Messinger’s book, Walls of Secrecy/Stories of Prison Life 1971-1981, paints a disturbing, tragic and frightening picture of that time behind bars, punctuated by slices of humanity and some humor.

Dick Morgan, the former director of corrections for the state, wrote the forward for the book and said Messinger’s narrative was an accurate portrayal of what life was like during what was known as the “Concrete Mama Era” at the penitentiary. That perspective was shared by his successor Steven Sinclair, who recently left the office. ”If you are a corrections professional or just question where corrections are today (Messinger’s book) is a must read. You can only understand how far we have come if you know where we have been.”

Messinger, a Vietnam veteran, survived by becoming part of the notorious biker gang in the prison and with not a small amount of luck. As Morgan wrote in his forward, “Kelley’s tenure at the penitentiary was a time prisoner well-being (and even survival) was determined entirely by prisoners, not staff.”

Kelley stopped by my office because he thinks the state needs to make some drastic changes in how it is handling prisoners. Messinger took the proverbial lemons of prison and made lemonade by focusing on getting educated, which gave him the opportunity to move on with his life after prison.

The state, Messinger said, would be better off providing educational opportunities for prisoners combined with an incentive program that encourages them to take it seriously. Right now, Messinger said, the state offers inmates time off of their sentence for good behavior — essentially not causing problems.

But a far more constructive approach would be to link reduced sentence time to their pursuit of education. “If it’s not done right, it will fail, just like it failed back in the 1970s,” said Messinger. “We have to incentivize the inmates so they want good education.”

Studies consistently show that education reduces recidivism, including the latest data from the Washington State Statistical Analysis Center. This makes logical sense. If those incarcerated walk out of prison with a GED or higher education degree, they’ll be more employable and less likely to reoffend.

Messinger continues to volunteer helping inmates who are struggling with mental health issues and who cannot get legal representation. If they’re judged mentally ill or mentally disabled, said Messinger, “there’s not a lawyer in town who will touch them.”

So Messinger helps out where he can. One of the dirty secrets of our prison system is the number of mentally ill people who are incarcerated and don’t get the help they need. This is the result of our decision years ago to dismantle the mental health institutions. Those individuals are now in jails and prisons to a great extent.

What inspires me about Messinger is his complete lack of bitterness about the wrongful conviction and the way he used his opportunity for education to move on after Gov. Ray commuted his sentence.

His perspective is sound, he speaks with authority and with a deep understanding of the dysfunction of our current system. He also brings a sense of humanity to the discussion.