Dividing Paradise: What I have learned about the social divide in rural communities

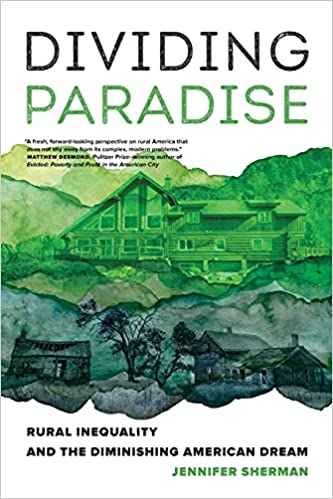

(Editor’s note: This is the third and final column focusing on the book: Dividing Paradise: Rural Inequality and the Diminishing American Dream by WSU sociologist Jennnifer Sherman)

We all have blind spots. We see the world from our own experience, education and background and deceive ourselves into thinking that our perspective is correct and the viewpoint of others is faulty.

That’s why it’s important to seek out different viewpoints and consider evidence that counters our thinking.

For example, I thought I had a pretty good understanding of the social dynamics of the Methow Valley and other recreational meccas in our region. After reading Dividing Paradise: Rural Inequality and the Diminishing American Dream by WSU sociologist Jennifer Sherman, I now see that my understanding has been limited and that I was blissfully ignorant of the plight of long-time residents who have become strangers in their own hometowns.

The book is based on Sherman’s time spent living in a mountain community she refers to as Paradise Valley, to maintain confidentiality. But it is an open secret that the research was done in the Methow Valley. In the book, she described the growing divide between old-timers and newcomers to the valley and their differing world views and life experiences.

In the book, she describes how in the early years of the Methow transformation from a agriculture, logging and ranching economy to one based on recreation, newcomers tended to integrate with the culture of the valley. Nowadays, it’s the newcomers who are the dominant force economically, socially and politically and long-term residents find themselves on the outside looking in.

The valley, as Sherman describes it, “is simultaneously a rural utopia of community and social support for some (the newcomers) and an increasingly divided community where disenfranchisement, misunderstanding and judgment dominate the social landscape for others (the old-timers).”

She did lengthy interviews with people representing a cross-section of the community. Reading the words as spoken by the people who live there (who are identified by pseudonyms for confidentiality), I came away with a whole different view of not just the social divide in the Methow, but also in the country.

One theme that emerged from Sherman’s book was the sense of pride and dignity of the long-term residents who used to make up the heart and soul of the community. As their fortunes diminished relative to the fantastic wealth of the newcomers, many have struggled to accept help that would make their lives easier. But these virtues of hard work and self sufficiency are not generally seen as worthy of respect by newcomers.

In terms of a sense of community, Sherman paints a vivid picture that newcomers and old-timers “envision and enact community differently,” which if you think about it makes sense.

They go to different cultural events, have different hobbies and interests, have vastly different financial wherewithal, etc.

Is it any wonder that the typically more conservative, less affluent, old-timers feel like aliens in their own communities — feeling dismissed or devalued by folks who moved in recently from big cities like Seattle, built expensive houses and who are insulated from financial challenges.

A significant challenge for civic leaders as well as nonprofits that are devoted to strengthening the community is to find creative ways to bring together individuals from both sides of the divide in ways that foster respect, trust and a shared sense of purpose.

What’s happening in the Methow is happening all over North Central Washington and the country. Until we see the value in other human beings who have different values and ideas, we will continue to live in communities divided.

Addressing this means seeing our own class blindness and taking steps to build meaningful relationships with those who have different views and experiences.